Tasmania’s salmon industry was overwhelmed by this year’s mass fish deaths, with no effective waste recovery systems or emergency plan in place when fatty substances from decomposing fish began washing up on southern beaches.

A government review found the mass mortality event – which unfolded between January and April in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel – exposed gaps in coordination between regulators and salmon companies, leaving agencies scrambling for information.

The “Reflections and Learnings” report, released by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment, concluded the outbreak was primarily driven by the bacterium Piscirickettsia salmonis, present in Tasmanian waters since at least 2021.

“The required mortality retrieval exceeded the industry’s mortality retrieval system capabilities,” the report found. “This was the root cause of the waste management issue.”

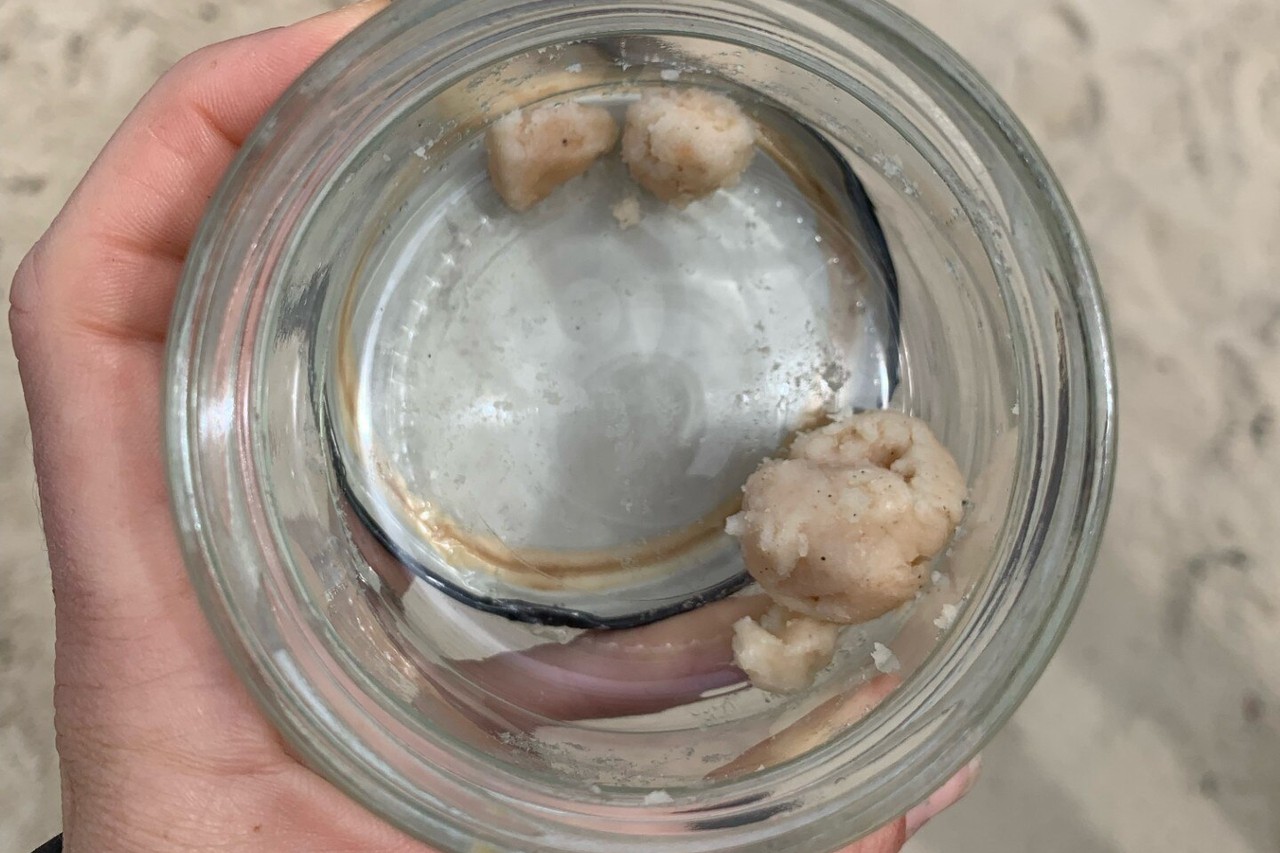

The incident directly affected Huon Aquaculture and Tassal, drawing national media attention as “mort balls” – fatty clumps from decomposing salmon – washed ashore and sparked public concern about pollution and food safety.

The incident directly affected Huon Aquaculture and Tassal, drawing intense national media attention as “mort balls” washed ashore – fatty clumps from decomposing salmon that sparked public concern about pollution and food safety.

While acknowledging the waste was an “unacceptable nuisance”, the report said the material “did not present any public health issues”.

Investigators identified a combination of environmental stressors, including warm summer conditions, jellyfish blooms and marine heatwave events.

“Marine waters off eastern Tasmania are warming nearly four times faster than the global average,” it stated, with sea surface temperatures up to 2.5 degrees above normal during February.

One of the most serious findings was the lack of a coordinated emergency response.

“In the absence of this plan and what agencies described as a lack of accurate timely advice from industry, communication and event coordination by government had duplication, initial role confusion and delayed critical decision-making,” the report found.

Agencies also reported that key details about the scale and duration of the crisis were not shared in time, eroding public trust.

Both industry and government staff described the months-long response as highly stressful.

“Government agency officers were often required to perform roles beyond their normal remit, while industry staff operated under the weight of operational pressure and intense public scrutiny,” the review found.

Despite rendering facilities remaining operational, the sheer number of dead fish overwhelmed existing infrastructure, leading to unauthorised discharges of controlled waste.

At the peak in February, only about 5% of mortality waste went to landfill.

The remainder was sent to rendering and ensilage plants, many of which struggled to meet compliance requirements.

The report set out 10 actions to prevent a repeat of the crisis, including developing a marine heatwave response plan, creating a coordinated emergency framework and boosting vaccine research capacity.

It also noted the antibiotic florfenicol is the preferred treatment method going forward, with the industry now seeking emergency approval for its use.

Prominent anti-salmon campaigner and independent MP Peter George said the report confirmed “a litany of industry and regulatory failure”.

He has called for penalties and possible prosecutions.

“Despite all the warning signs of disease, infestations and increasing mortalities neither industry nor the government had any plans in place to deal with the crisis,” he said.

“I call on the government to immediately increase regulatory control, including increased staff, resources and vessels to ensure a truly independent monitoring of an out-of-control industry.”

“The extra costs to government should be covered by industry imposts and increased licence costs.”